Biodiversity conservation science, from local to global...

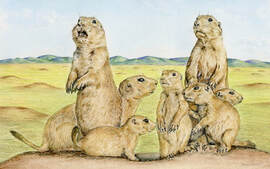

PBS interview on prairie dog ecology and conservation

Research Themes:

- Ecology and Conservation of Burrowing Mammals in the World's Grasslands

- Grassland Ecology and Mammalian Herbivores in Working Landscapes

- Human-Wildlife Coexistence

- Conservation Planning

- Restoration Ecology

- Global Conservation, Biogeography, and Macroecology

Current Projects:

- Participatory Research to Quantify Prairie Dog Impacts on Livestock Production in Western Rangelands, Thunder Basin National Grassland, WY

- Understanding How to Manage Prairie Dog Population Dynamics in the Context of Plague, Climate, and Livestock Production

- Developing Innovative Solutions for Human-Bison Coexistence across North America

- Cross-continental Research on the Impacts of Burrowing Mammals on Invertebrate Biodiversity and Function

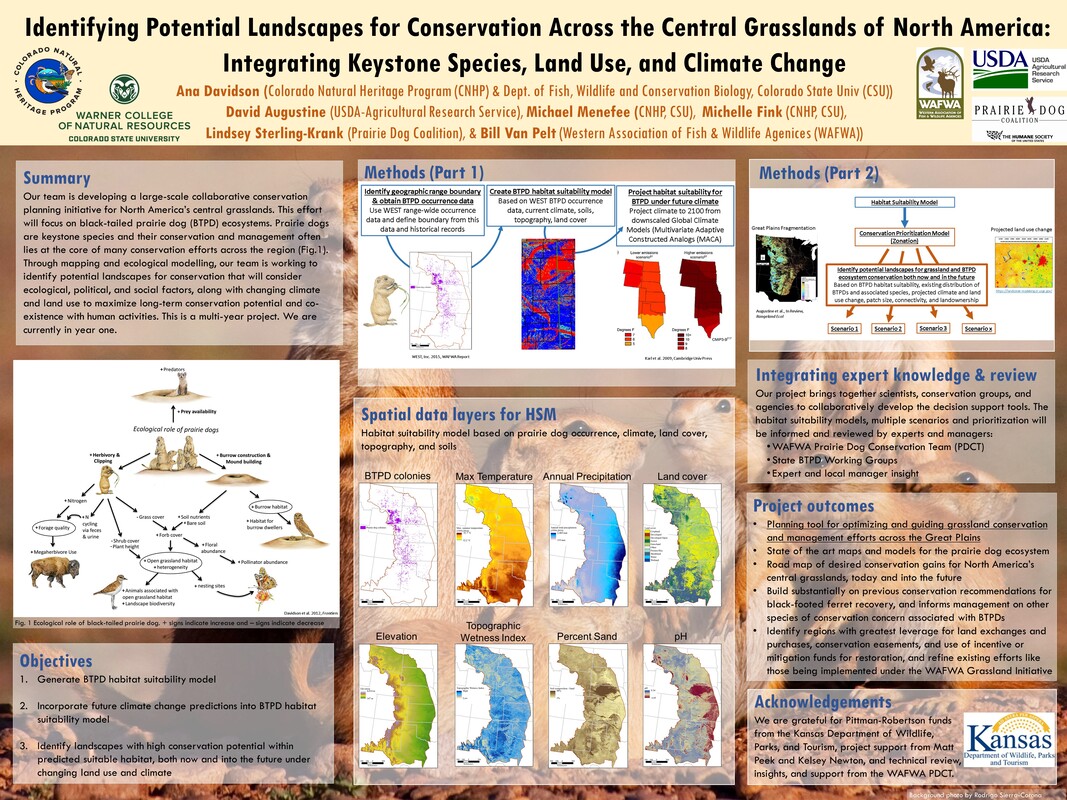

- Identifying Potential Landscapes for Conservation Across the Central Grasslands of North America: Integrating Keystone Species, Land Use, Social Acceptance, and Climate Change

Ecology and Conservation of Burrowing Mammals in the World's Grasslands

Davidson et al. 2012, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment

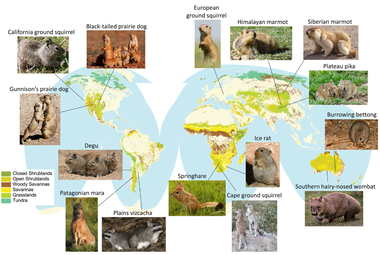

The world’s grasslands are fundamentally shaped by an underappreciated key functional group of social, semi-fossorial, herbivorous mammals. Examples include the phylogentically similar species of prairie dogs of North America (NA) (Cynomys spp.), ground squirrels (Sciuridae spp.) of NA, Eurasia, and Africa, and marmots (Marmota spp.) of NA and Eurasia, but also more distantly related but functionally similar plains vizcachas (Lagostomus maximus), Patagonian maras (Dolichotis patagonum) and degus (Octodon degus) of South America, pikas (Ochotona spp.) of Asia, ice rats (Otomys sloggetti) and springhares (Pedetes capensis) of Africa, and burrowing bettongs (Bettongia lesueur) and southern hairy-nosed wombats (Lasiorhinus latifrons) of Australia. These burrowing mammals often live in colonies ranging from 10s to 1000s of individuals. They collectively transform grassland landscapes through their burrowing and herbivory, and by grouping together socially, they create distinctive habitat patches that serve as areas of concentrated prey for many predators.

Yet, burrowing mammal populations have declined dramatically because of human impacts. Indeed, because grasslands provide the world’s most important habitat for agricultural and livestock production, burrowing mammals are often in direct conflict with human activities. Human-mediated introductions of exotic species, including disease-causing organisms, and overhunting are also reducing their populations. What we know about the few well-studied species suggests that burrowing mammals likely play widespread and important ecological roles, and that their loss can have cascading effects on grassland ecosystems on which both humans and wildlife depend. My research seeks to address these challenges facing prairie dogs and associated species in the central grasslands of North America, and incorporates the ecological, social, economic, and human dimensions.

Yet, burrowing mammal populations have declined dramatically because of human impacts. Indeed, because grasslands provide the world’s most important habitat for agricultural and livestock production, burrowing mammals are often in direct conflict with human activities. Human-mediated introductions of exotic species, including disease-causing organisms, and overhunting are also reducing their populations. What we know about the few well-studied species suggests that burrowing mammals likely play widespread and important ecological roles, and that their loss can have cascading effects on grassland ecosystems on which both humans and wildlife depend. My research seeks to address these challenges facing prairie dogs and associated species in the central grasslands of North America, and incorporates the ecological, social, economic, and human dimensions.

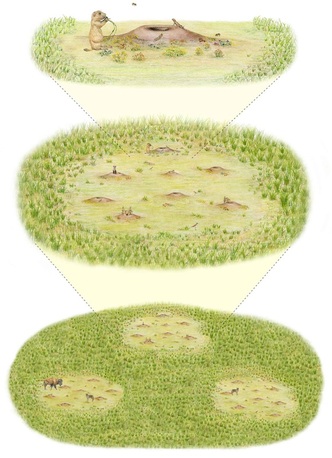

Islands of Habitat

Diagram illustrating the distinctive islands of habitat that burrowing mammals create across multiple spatial scales with their mounds (top), individual colonies (middle), and colony complexes (bottom), resulting in increased habitat heterogeneity and biodiversity across the landscape. This illustration is based on black-tailed prairie dogs in the Great Plains grasslands of NA. Drawing is by Sharyn N. Davidson. (Davidson et al. 2012, Frontiers)

|

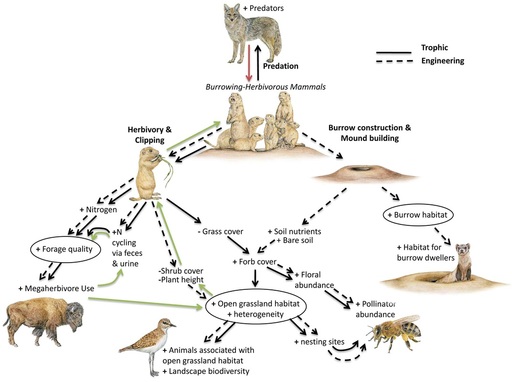

Ecological Role

Conceptual diagram showing the trophic (herbivory, prey) and ecosystem engineering (clipping, burrow construction, and mound building) effects of burrowing mammals on the grassland ecosystem, based on the roles of the best-studied species: the black-tailed prairie dog (C. ludovicianus) in NA. Plus signs indicate an increase, minus signs indicate a decrease. Black arrows depict the effects of burrowing mammals (e.g., prairie dogs), green arrows depict the impacts of megaherbivores (e.g., bison), and the red arrow indicates the role of predators. Drawings are by Sharyn N. Davidson. (Davidson et al. 2012, Frontiers)

|

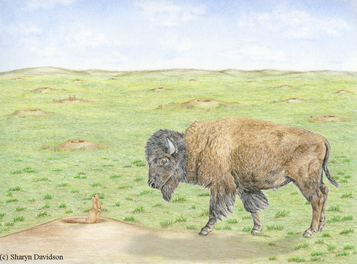

Prairie dogs (Cynomys spp.) play important roles in shaping the central grasslands of North America. By grazing and clipping vegetation they create a low mat of dense forbs and grazing tolerant grasses, and dot the landscape with numerous mounds. Their colonies represent unique islands of open grassland habitat that attract numerous animals, such as burrowing owls and mountain plovers (Charadrius montanus), and predators that rely on prairie dogs as a primary food source, such as coyotes, American badgers (Taxidea taxus), raptors, and the highly endangered black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes). Although the magnitude of these impacts can vary by prairie dog species, colony density, or other site-specific factors, prairie dogs play important ecological roles in grasslands across their range.

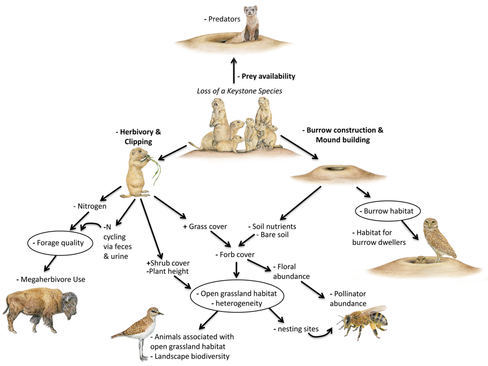

Prairie dog populations have declined by about 98% over the last century, and are consequently identified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need by the state of New Mexico. Much of their decline is due to poisoning, introduced sylvatic plague, habitat loss, shooting 6, and increasingly, climate change in the southern portion of their range. The dramatic decline in prairie dogs has resulted in consequent losses in associated species and grassland habitat. Indeed, because prairie dog populations have undergone severe numerical reductions, their key ecological roles have been greatly diminished throughout much of their geographic range. Loss of prairie dogs has resulted in declines in species associated with the habitats they create, including the burrowing owl and mountain plover, and those dependent or heavily reliant upon prairie dogs as prey, including black-footed ferrets and ferruginous hawks (Buteo regalis). Additionally, grasslands have been invaded by shrubs in areas where black-tailed prairie dogs (C. ludovicianus) have been poisoned in the southern distribution of their range, demonstrating their role in maintaining grasslands and the ecosystem services they provide to humans. Prairie dogs are needed in large numbers across the greater grassland landscape in order to support associated species and maintain the unique islands of important grassland habitat and associated biodiversity. Because of their ecological importance there is much interest in restoring and protecting their populations. In fact, the USFWS black-footed ferret recovery plan specifically states, “We believe the single, most feasible action that would benefit black-footed ferret recovery is to improve prairie dog conservation. If efforts were undertaken to more proactively manage existing prairie dog habitat for ferret recovery, all other threats to the species would be substantially less difficult to address”

Prairie dog populations have declined by about 98% over the last century, and are consequently identified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need by the state of New Mexico. Much of their decline is due to poisoning, introduced sylvatic plague, habitat loss, shooting 6, and increasingly, climate change in the southern portion of their range. The dramatic decline in prairie dogs has resulted in consequent losses in associated species and grassland habitat. Indeed, because prairie dog populations have undergone severe numerical reductions, their key ecological roles have been greatly diminished throughout much of their geographic range. Loss of prairie dogs has resulted in declines in species associated with the habitats they create, including the burrowing owl and mountain plover, and those dependent or heavily reliant upon prairie dogs as prey, including black-footed ferrets and ferruginous hawks (Buteo regalis). Additionally, grasslands have been invaded by shrubs in areas where black-tailed prairie dogs (C. ludovicianus) have been poisoned in the southern distribution of their range, demonstrating their role in maintaining grasslands and the ecosystem services they provide to humans. Prairie dogs are needed in large numbers across the greater grassland landscape in order to support associated species and maintain the unique islands of important grassland habitat and associated biodiversity. Because of their ecological importance there is much interest in restoring and protecting their populations. In fact, the USFWS black-footed ferret recovery plan specifically states, “We believe the single, most feasible action that would benefit black-footed ferret recovery is to improve prairie dog conservation. If efforts were undertaken to more proactively manage existing prairie dog habitat for ferret recovery, all other threats to the species would be substantially less difficult to address”

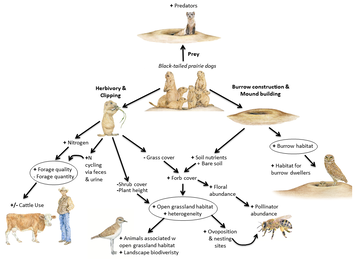

Cascading effects of keystone species declines

Conceptual diagram illustrating how the loss of a keystone species cascades throughout an ecosystem, using the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) in North America’s central grasslands as an example. Declines in prairie dogs result in the loss of their trophic (herbivory, prey) and ecosystem engineering (clipping, burrow construction, and mound building) effects on the grassland, with consequent declines in predators [e.g., black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes), raptors, swift and kit foxes (Vulpes velox, V. macrotis), coyotes (Canis latrans), badgers (Taxidea taxus)], large activity [e.g., Bison (Bison bison)], invertebrate pollinators, and species that associate with the open habitats and burrows that they create [e.g., burrowing owls, (Athene cunicularia), mountain plovers (Charadrius montanus), pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), swift and kit foxes, cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.), rodents, and many species of herpetofauna and invertebrates]. Black arrows depict the effects of prairie dogs. Plus signs indicate an increase in an ecosystem property as a result of the loss of prairie dogs, minus signs indicate a decrease. Drawings are by Sharyn N. Davidson. (Figure taken from Bergstrom et al. 2013)

Cross-continental research on the impacts of burrowing mammals on invertebrate biodiversity and function

Current Project

Heloise Gibb, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Ana Davidson, Colorado State University (CSU)

Worldwide, digging mammals are suffering population declines as a result of anthropogenic causes, including species invasions, habitat destruction and direct persecution. Digging mammals perform important functions in ecosystems, turning over vast quantities of soil every year. Further, they often play key trophic roles in ecosystems. However, little is known of the impacts of digging mammals on invertebrate and microbe communities or the ecosystem functions they perform. Further, it is unclear what responses may be general and which are conditional on the environmental conditions or taxa involved. We aim to determine how digging mammals affect biodiversity and function, using a set of sites along a rainfall gradient within Australia and a comparable system in the USA, the Central Plains Experimental Range at the Pawnee National Grassland in northern Colorado. We are using a key set of indicators, including: a) spider and ant assemblage composition; b) nitrogen isotopes of soils, vegetation and herbivorous, omnivorous and predatory insects; c) microbial decomposition enzymes; and d) litter bag decomposition.

Current Project

Heloise Gibb, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Ana Davidson, Colorado State University (CSU)

Worldwide, digging mammals are suffering population declines as a result of anthropogenic causes, including species invasions, habitat destruction and direct persecution. Digging mammals perform important functions in ecosystems, turning over vast quantities of soil every year. Further, they often play key trophic roles in ecosystems. However, little is known of the impacts of digging mammals on invertebrate and microbe communities or the ecosystem functions they perform. Further, it is unclear what responses may be general and which are conditional on the environmental conditions or taxa involved. We aim to determine how digging mammals affect biodiversity and function, using a set of sites along a rainfall gradient within Australia and a comparable system in the USA, the Central Plains Experimental Range at the Pawnee National Grassland in northern Colorado. We are using a key set of indicators, including: a) spider and ant assemblage composition; b) nitrogen isotopes of soils, vegetation and herbivorous, omnivorous and predatory insects; c) microbial decomposition enzymes; and d) litter bag decomposition.

Keystone Species Interactions: Separate and Interactive Effects of Prairie Dogs and Banner-Tailed Kangaroo Rats on Plants and Animals in the Chihuahuan Desert Grasslands

Past Project

A fundamental goal of ecology is to understand the underlying mechanisms that regulate community structure and biodiversity. In many ecosystems, certain species play a central role in the organization of communities. These species are often referred to as keystones, and are defined by having distinctive and disproportionately large impacts on community structure and ecosystem function relative to their abundance. Such species can affect ecosystems through a variety of processes, from top-down effects through the consumption of prey to bottom-up effects through ecosystem engineering. Although keystone species co-occur in many systems, their interactive effects have received little attention.

For my dissertation, under the advisorship of Jim Brown and in collaboration with Dr. David Lightfoot, I evaluated the separate and interactive effects of prairie dogs (C. gunnisoni and C. ludovicianus) and banner-tail kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spectabilis) on plants, arthropods, and lizards. I found that the impacts of prairie dogs and kangaroo rats were unique, and the habitats they created supported different assemblages of plants and arthropods, and lizards. Where both rodent species co-occurred, there was greater heterogeneity and species diversity on the landscape. These results suggest that the interaction of multiple keystones, especially those with engineering roles, results in unique and more diverse communities in time and space (Davidson and Lightfoot 2006, Ecog.; 2007, Ecog.; 2008, JAE; and Davidson et al. 2008, JAE).

For my dissertation, under the advisorship of Jim Brown and in collaboration with Dr. David Lightfoot, I evaluated the separate and interactive effects of prairie dogs (C. gunnisoni and C. ludovicianus) and banner-tail kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spectabilis) on plants, arthropods, and lizards. I found that the impacts of prairie dogs and kangaroo rats were unique, and the habitats they created supported different assemblages of plants and arthropods, and lizards. Where both rodent species co-occurred, there was greater heterogeneity and species diversity on the landscape. These results suggest that the interaction of multiple keystones, especially those with engineering roles, results in unique and more diverse communities in time and space (Davidson and Lightfoot 2006, Ecog.; 2007, Ecog.; 2008, JAE; and Davidson et al. 2008, JAE).

Grassland Ecology and Mammalian Herbivores in Working Landscapes

Grasslands are among the most imperiled ecosystems in the world due to agricultural intensification, desertification, and the loss of native species. In order to manage and conserve these systems in the face of multiple, and often conflicting interests, there is a critical need to understand the mechanisms that drive grassland ecosystem dynamics and biodiversity.

Megaherbivores and small burrowing mammals are known to play key roles in the structure and function of grasslands worldwide. Although domestic livestock have replaced native megaherbivores throughout much of the world, surprisingly little is known about their interactive effects with native wildlife and the consequent effects on grassland ecosystems.

A critical issue for conservation of grasslands around the world is the need to maintain the important functional role of keystone burrowing mammals, like prairie dogs, while simultaneously managing for livestock production. Competition with cattle has been used to justify extensive programs to eradicate prairie dogs and other herbivorous rodents from grasslands throughout the world. In the U.S., a century of prairie dog “pest control” programs have been largely responsible for reducing their populations to 2-5% of their historic numbers, and these control efforts still continue today.

Megaherbivores and small burrowing mammals are known to play key roles in the structure and function of grasslands worldwide. Although domestic livestock have replaced native megaherbivores throughout much of the world, surprisingly little is known about their interactive effects with native wildlife and the consequent effects on grassland ecosystems.

A critical issue for conservation of grasslands around the world is the need to maintain the important functional role of keystone burrowing mammals, like prairie dogs, while simultaneously managing for livestock production. Competition with cattle has been used to justify extensive programs to eradicate prairie dogs and other herbivorous rodents from grasslands throughout the world. In the U.S., a century of prairie dog “pest control” programs have been largely responsible for reducing their populations to 2-5% of their historic numbers, and these control efforts still continue today.

Participatory Research to Quantify Prairie Dog Impacts on Livestock Production in Western Rangelands, Thunder Basin National Grassland, WY

Current Project

Ana Davidson, CSU

Lauren Porensky, USDA-Agricultural Research Service (ARS)

David Augustine, USDA-ARS

Justin Derner, USDA-ARS

David Pellatz, Thunder Basin Grasslands Prairie Ecosystem Association

J. Derek Scasta, University of Wyoming

Greg Newman, CSU

Rationale, Goal and Objectives. Competition between livestock and prairie dogs is a widely discussed, but poorly understood barrier to livestock production in western North American rangelands. Wildlife conservation efforts have led to increases in prairie dog populations across public and private rangelands in western rangelands over the past two decades. For land managers striving to balance dual objectives of livestock production and conservation, there is an urgent need for quantitative measures of prairie dog impacts on livestock production. In one of the only quantitative studies on this subject, Derner et al. (2006) found that prairie dogs can reduce livestock value by up to $38 per steer and $5.58 per hectare for the summer grazing season. Yet, other analyses indicate prairie dogs can enhance livestock performance under certain weather and vegetation conditions. A comprehensive review of the subject concluded: “Large-scale field studies - involving numerous pastures, with and without prairie dogs, are necessary to clarify the effects of prairie dogs on domestic livestock. With so much controversy and so many economic implications, the paucity of such studies is disappointing” (Detling 2006). We are conducting an integrated, participatory research approach to quantify prairie dog effects on livestock production, and develop trusted decision-support tools for managers and stakeholders that optimize both livestock production and grassland ecosystem conservation. Our specific objectives are to: 1) Integrate livestock producers in the design, implementation, and execution of research on the critical stakeholder-identified issue of prairie dog-livestock competition; 2) Quantify relationships between cattle weight gains and prairie dog abundance at pasture scales, across multiple years; 3) Evaluate whether the spatiotemporal pattern of livestock grazing can mechanistically explain how prairie dog abundance and distribution affect livestock weight gains; 4) Determine if stakeholder participation in our research design and execution alters their trust in, and perceptions of, the scientific results from this research; and 5) Co-create with stakeholders decision support tools.

Current Project

Ana Davidson, CSU

Lauren Porensky, USDA-Agricultural Research Service (ARS)

David Augustine, USDA-ARS

Justin Derner, USDA-ARS

David Pellatz, Thunder Basin Grasslands Prairie Ecosystem Association

J. Derek Scasta, University of Wyoming

Greg Newman, CSU

Rationale, Goal and Objectives. Competition between livestock and prairie dogs is a widely discussed, but poorly understood barrier to livestock production in western North American rangelands. Wildlife conservation efforts have led to increases in prairie dog populations across public and private rangelands in western rangelands over the past two decades. For land managers striving to balance dual objectives of livestock production and conservation, there is an urgent need for quantitative measures of prairie dog impacts on livestock production. In one of the only quantitative studies on this subject, Derner et al. (2006) found that prairie dogs can reduce livestock value by up to $38 per steer and $5.58 per hectare for the summer grazing season. Yet, other analyses indicate prairie dogs can enhance livestock performance under certain weather and vegetation conditions. A comprehensive review of the subject concluded: “Large-scale field studies - involving numerous pastures, with and without prairie dogs, are necessary to clarify the effects of prairie dogs on domestic livestock. With so much controversy and so many economic implications, the paucity of such studies is disappointing” (Detling 2006). We are conducting an integrated, participatory research approach to quantify prairie dog effects on livestock production, and develop trusted decision-support tools for managers and stakeholders that optimize both livestock production and grassland ecosystem conservation. Our specific objectives are to: 1) Integrate livestock producers in the design, implementation, and execution of research on the critical stakeholder-identified issue of prairie dog-livestock competition; 2) Quantify relationships between cattle weight gains and prairie dog abundance at pasture scales, across multiple years; 3) Evaluate whether the spatiotemporal pattern of livestock grazing can mechanistically explain how prairie dog abundance and distribution affect livestock weight gains; 4) Determine if stakeholder participation in our research design and execution alters their trust in, and perceptions of, the scientific results from this research; and 5) Co-create with stakeholders decision support tools.

Understanding How to Manage Prairie Dog Population Dynamics in the Context Of Plague, Climate, and Livestock Production

Current Project

Ana Davidson, CSU

David Augustine, USDA-ARS

Kevin Shoemaker, University of Nevada, Reno

Cynthia Hartway, Wildlife Conservation Society

Lauren Porensky, USDA-ARS

Justin Derner, USDA-ARS

Throughout their western range, prairie dog populations cycle through alternating periods of expansion and collapse, presenting pressing and complex challenges for rangeland management. The expansion phase of prairie dog colonies inevitably leads to conflicts with livestock production, while their collapse raises concerns for the abundance and persistence of prairie dog-associated wildlife. The opposing and alternating effects of these boom-bust cycles result in economic losses, biodiversity losses, and persistent human-wildlife conflicts. Ensuring the long-term sustainability of rangeland systems requires developing effective strategies for managing these boom-bust cycles, yet the social, demographic, and environmental factors driving these cycles and how to manage them remain poorly understood. This study will address key knowledge gaps related to the drivers of prairie dog boom-bust cycles and the effects of these cycles on sustainable livestock production, biodiversity, and rangeland health. Specifically, this project will (1) investigate how ecological, social, and climate variables drive prairie dog colony dynamics over time and space; (2) determine how prairie dog colony size interacts with environmental covariates to affect important rangeland ecosystem services (livestock production, soil health, and biodiversity); and (3) use this information to develop a predictive model and decision support tool to inform best practices for rangeland management. Understanding the drivers of prairie dog colony dynamics and the many ecosystem processes they affect will lead to novel and targeted management solutions that dampen these harmful boom-bust cycles and ultimately promote biodiversity, livestock production, ecosystem sustainability, and overall rangeland health.

Current Project

Ana Davidson, CSU

David Augustine, USDA-ARS

Kevin Shoemaker, University of Nevada, Reno

Cynthia Hartway, Wildlife Conservation Society

Lauren Porensky, USDA-ARS

Justin Derner, USDA-ARS

Throughout their western range, prairie dog populations cycle through alternating periods of expansion and collapse, presenting pressing and complex challenges for rangeland management. The expansion phase of prairie dog colonies inevitably leads to conflicts with livestock production, while their collapse raises concerns for the abundance and persistence of prairie dog-associated wildlife. The opposing and alternating effects of these boom-bust cycles result in economic losses, biodiversity losses, and persistent human-wildlife conflicts. Ensuring the long-term sustainability of rangeland systems requires developing effective strategies for managing these boom-bust cycles, yet the social, demographic, and environmental factors driving these cycles and how to manage them remain poorly understood. This study will address key knowledge gaps related to the drivers of prairie dog boom-bust cycles and the effects of these cycles on sustainable livestock production, biodiversity, and rangeland health. Specifically, this project will (1) investigate how ecological, social, and climate variables drive prairie dog colony dynamics over time and space; (2) determine how prairie dog colony size interacts with environmental covariates to affect important rangeland ecosystem services (livestock production, soil health, and biodiversity); and (3) use this information to develop a predictive model and decision support tool to inform best practices for rangeland management. Understanding the drivers of prairie dog colony dynamics and the many ecosystem processes they affect will lead to novel and targeted management solutions that dampen these harmful boom-bust cycles and ultimately promote biodiversity, livestock production, ecosystem sustainability, and overall rangeland health.

Dr. Gabe Barrile recently joined our team! He is a postdoctoral researcher for this project.

We are excited to have him on board.

Gabe recently earned a Ph.D. in Ecology (May 2021) from the University of Wyoming, where he was hosted by the Department of Zoology and Physiology and the Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. His doctoral research investigated the behavioral and demographic responses of amphibian populations to infectious disease and various forms of environmental change. Gabe currently works as a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Quantitative Ecology at the Colorado Natural Heritage Program at Colorado State University. His research seeks to better understand the boom-and-bust cycles of black-tailed prairie dogs in the context of climate and sylvatic plague, as well as the implications of those dynamics for livestock production and wildlife conservation in grassland ecosystems. Gabe plans to remain at the interface of basic and applied science by conducting research that both advances ecological theory and helps to develop practical solutions to conservation challenges.

We are excited to have him on board.

Gabe recently earned a Ph.D. in Ecology (May 2021) from the University of Wyoming, where he was hosted by the Department of Zoology and Physiology and the Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. His doctoral research investigated the behavioral and demographic responses of amphibian populations to infectious disease and various forms of environmental change. Gabe currently works as a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Quantitative Ecology at the Colorado Natural Heritage Program at Colorado State University. His research seeks to better understand the boom-and-bust cycles of black-tailed prairie dogs in the context of climate and sylvatic plague, as well as the implications of those dynamics for livestock production and wildlife conservation in grassland ecosystems. Gabe plans to remain at the interface of basic and applied science by conducting research that both advances ecological theory and helps to develop practical solutions to conservation challenges.

Developing Innovative Solutions for Human-Bison Coexistence across North America

Current Project

Ana Davidson, CSU

Liba Pejchar, CSU

Jennifer Barfield, CSU

Cynthia Hartway, Wildlife Conservation Society & South Dakota State University

Rebecca Niemiec, CSU

Lissett Medrano, CSU

Bison are an iconic and ecologically important species, but occupy less than 1% of their historic range. The reintroduction and management of bison are among the most challenging human-wildlife coexistence issues today in North America, yet there is widespread interest in restoring this iconic species across the American West. Public, private and tribal land managers have identified bison reintroduction as a priority to ensure viable free-roaming populations, restore ecological function, and enhance cultural values. Currently, reintroduction of free-roaming bison is fraught with concerns over the transmission of disease to livestock, competition with cattle for shared forage, and uncertainty about the ecological impact of bison on arid ecosystems. With support from Colorado State University, our team came together to explore the ecological, economic, social, and cultural dimensions of this timely and continental-scale challenge, and propose an agenda for research and action.

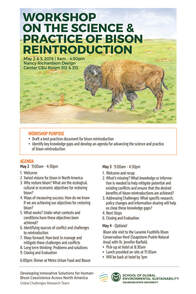

In May 2019, we hosted a two-day technical workshop that brought together 33 practitioners and scholars from the US, Canada and Mexico with expertise in bison reintroduction and management (Fig. 1). Through bringing together this diverse group of experts, the workshop served to address knowledge gaps in the management of bison including key policy, communication and research needs. Our working group identified that a stronger and more connected network of bison scientists and practitioners was greatly needed to facilitate bison restoration across North America, and suggested two different national-scale groups should form: 1) a bison working group consisting of scientists and practitioners to facilitate shared learning across diverse regions and contexts, and 2) a national advocacy and funding organization to increase social acceptance, awareness and interest in bison conservation. We also developed an online survey to reach a broader audience of bison experts with themes focused on the challenges, keys to success and research needs. The survey was sent to over 200 experts and we received approximately 80 responses, primarily from practitioners within the government, non-profit and academic sectors. Preliminary results found the top challenges to restoration to be social acceptability, political will, and ability to work across stakeholder groups. As a next step, we will submit a manuscript summarizing key needs, knowledge gaps, and future directions for bison reintroduction to a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Below is our presentation we presented at America's Grasslands Conference in Bismark, North Dakota, August, 2019 and at the American Bison Society meeting in Santa Fe, New Mexico October 2019.

Current Project

Ana Davidson, CSU

Liba Pejchar, CSU

Jennifer Barfield, CSU

Cynthia Hartway, Wildlife Conservation Society & South Dakota State University

Rebecca Niemiec, CSU

Lissett Medrano, CSU

Bison are an iconic and ecologically important species, but occupy less than 1% of their historic range. The reintroduction and management of bison are among the most challenging human-wildlife coexistence issues today in North America, yet there is widespread interest in restoring this iconic species across the American West. Public, private and tribal land managers have identified bison reintroduction as a priority to ensure viable free-roaming populations, restore ecological function, and enhance cultural values. Currently, reintroduction of free-roaming bison is fraught with concerns over the transmission of disease to livestock, competition with cattle for shared forage, and uncertainty about the ecological impact of bison on arid ecosystems. With support from Colorado State University, our team came together to explore the ecological, economic, social, and cultural dimensions of this timely and continental-scale challenge, and propose an agenda for research and action.

In May 2019, we hosted a two-day technical workshop that brought together 33 practitioners and scholars from the US, Canada and Mexico with expertise in bison reintroduction and management (Fig. 1). Through bringing together this diverse group of experts, the workshop served to address knowledge gaps in the management of bison including key policy, communication and research needs. Our working group identified that a stronger and more connected network of bison scientists and practitioners was greatly needed to facilitate bison restoration across North America, and suggested two different national-scale groups should form: 1) a bison working group consisting of scientists and practitioners to facilitate shared learning across diverse regions and contexts, and 2) a national advocacy and funding organization to increase social acceptance, awareness and interest in bison conservation. We also developed an online survey to reach a broader audience of bison experts with themes focused on the challenges, keys to success and research needs. The survey was sent to over 200 experts and we received approximately 80 responses, primarily from practitioners within the government, non-profit and academic sectors. Preliminary results found the top challenges to restoration to be social acceptability, political will, and ability to work across stakeholder groups. As a next step, we will submit a manuscript summarizing key needs, knowledge gaps, and future directions for bison reintroduction to a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Below is our presentation we presented at America's Grasslands Conference in Bismark, North Dakota, August, 2019 and at the American Bison Society meeting in Santa Fe, New Mexico October 2019.

Facilitating Coexistence and Disentangling the Ecological Impacts of Prairie Dogs and Cattle in the Janos Grasslands of Northern Chihuahua, Mexico

Past Project

Ana Davidson, UNAM

Eduardo Ponce, UNAM

David Lightfoot, UNM

Rodrigo Sierra-Corona, UNAM

Ed Fredrickson, USDA-ARS

James H. Brown, UNM

Gerardo Ceballos, UNAM

I established a long-term, large-scale experiment in the Janos grasslands, Chihuahua, Mexico that simultaneously manipulates both cattle and prairie dogs (C. ludovicianus), for my postdoctoral research under the advisement of Drs. Gerardo Ceballos and James H. Brown. The goal of this work is to help elucidate the relationships and interactive roles of these important herbivores, key to understanding the impact of human activities on global grassland decline and implementing proper management. This work is in collaboration with a team of researchers from the National University of Mexico (UNAM), the University of New Mexico (UNM), and the United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS). Our research shows that prairie dogs and cattle can have mutually beneficial relationships similar to the mutualistic relationship between prairie dogs and bison, and their combined effect on the grassland ecosystem can be synergistic (Davidson et al. 2010, Ecology; Sierra-Corona et al. 2015, PLOS ONE). We are also finding that the ecological relationship between cattle and prairie dogs in arid grasslands may be used strategically to help grow prairie dog colonies and reduce shrub invasion (Ponce et al. 2016, PLOS ONE).

Ana Davidson, UNAM

Eduardo Ponce, UNAM

David Lightfoot, UNM

Rodrigo Sierra-Corona, UNAM

Ed Fredrickson, USDA-ARS

James H. Brown, UNM

Gerardo Ceballos, UNAM

I established a long-term, large-scale experiment in the Janos grasslands, Chihuahua, Mexico that simultaneously manipulates both cattle and prairie dogs (C. ludovicianus), for my postdoctoral research under the advisement of Drs. Gerardo Ceballos and James H. Brown. The goal of this work is to help elucidate the relationships and interactive roles of these important herbivores, key to understanding the impact of human activities on global grassland decline and implementing proper management. This work is in collaboration with a team of researchers from the National University of Mexico (UNAM), the University of New Mexico (UNM), and the United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS). Our research shows that prairie dogs and cattle can have mutually beneficial relationships similar to the mutualistic relationship between prairie dogs and bison, and their combined effect on the grassland ecosystem can be synergistic (Davidson et al. 2010, Ecology; Sierra-Corona et al. 2015, PLOS ONE). We are also finding that the ecological relationship between cattle and prairie dogs in arid grasslands may be used strategically to help grow prairie dog colonies and reduce shrub invasion (Ponce et al. 2016, PLOS ONE).

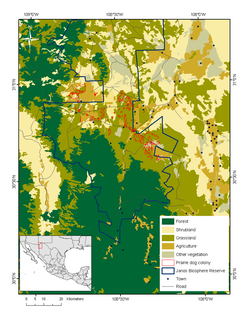

Janos Biosphere Reserve

Map of the Janos Biosphere Reserve

Our research group at UNAM led the establishment of the Janos Biosphere Reserve, which was decreed in 2009. It covers one million hectares in northern Mexico, and borders the United States. The reserve supports one of the largest remaining colony complexes of black-tailed prairie dogs, and a high diversity of threatened and endangered wildlife, including bison and black-footed ferrets.

Yet, pressures from cattle grazing, agricultural development, and climate change are seriously threatening the biodiversity of this region (Ceballos et al. 2010, PLoS ONE). The Janos Prairie Dog and Cattle Study is a part of the much broader conservation and research effort to restore and sustainably manage this grassland system. The approach is to recognize human well-being and the local agricultural community as an integral part of the ecological system and conservation strategy.

Yet, pressures from cattle grazing, agricultural development, and climate change are seriously threatening the biodiversity of this region (Ceballos et al. 2010, PLoS ONE). The Janos Prairie Dog and Cattle Study is a part of the much broader conservation and research effort to restore and sustainably manage this grassland system. The approach is to recognize human well-being and the local agricultural community as an integral part of the ecological system and conservation strategy.

Conservation Planning

Range-wide identification of priority areas for the conservation of North America’s central grasslands

Current Project

Ana Davidson, CSU

David Augustine, USDA-Agricultural Research Service

Michael Menefee, CSU

Lindsey Sterling-Krank, Prairie Dog Coalition

Bill Van Pelt, Western Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA)

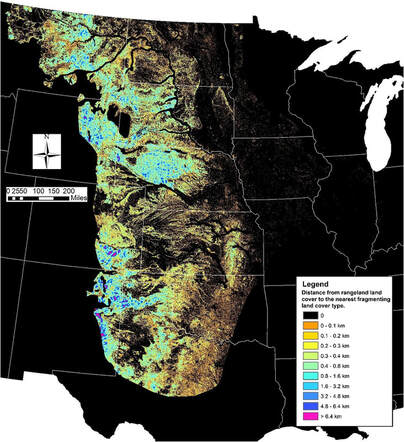

Our team is developing a large-scale collaborative conservation planning initiative for North America’s central grasslands. This effort will focus on black-tailed prairie dog (BTPD) ecosystems. Prairie dogs are keystone species and their conservation and management often lies at the core of many conservation efforts across the region. Through mapping and ecological modelling, our team is working to identify potential landscapes for conservation that will consider ecological, political, and social factors, along with changing climate and land use to maximize long-term conservation potential and co-existence with human activities. This is a multi-year project, and we are currently in year one. Our primary goals are to: 1) generate a BTPD habitat suitability model; 2) incorporate future climate change predictions into a BTPD habitat suitability model; and 3) identify landscapes with high conservation potential within predicted suitable habitat, both now and into the future, under changing land use and climate.

Our project brings together scientists, conservation groups, and agencies to collaboratively develop the decision support tools. The habitat suitability models, multiple scenarios and prioritization will be informed and reviewed by experts and managers, including the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ (WAFWA) Prairie Dog Conservation Team (PDCT), State BTPD Working Groups, and Expert and local manager insight. We aim to co-create a planning tool for optimizing and guiding grassland conservation and management efforts across the Great Plains, using state of the art maps and models for the prairie dog ecosystem. The planning tool will help provide a road map of desired conservation gains for North America’s central grasslands. This work will build substantially on previous conservation recommendations for black-footed ferret recovery, and inform management on other species of conservation concern associated with BTPDs. Additionally, it will identify regions with greatest leverage for land exchanges and purchases, conservation easements, and use of incentive or mitigation funds for restoration, and refine existing efforts like those being implemented under the WAFWA Grassland Initiative Planning tool for optimizing and guiding grassland conservation and management efforts across the Great Plains.

Below is our poster we presented at the America's Grasslands Conference in Bismark, ND in August 2019.

Thinking Like a Grassland: Challenges and Opportunities for Biodiversity Conservation in the Great Plains of North America

Recent Project

Augustine et al. 2019, Rangeland Ecology and Management

David Augustine, USDA-ARS

Ana Davidson, CSU

Kristin Dickinson, USDA-NRCS

Bill Van Pelt, WAFWA

Fauna of North America’s Great Plains evolved strategies to contend with the region’s extreme spatiotemporal variability in weather and low annual primary productivity. The capacity for large-scale movement (migration and/or nomadism) enables many species, from bison to lark buntings, to track pulses of productivity at broad spatial scales (> 1 000 km2). Furthermore, even sedentary species often rely on metapopulation dynamics over extensive landscapes for long-term population viability. The current complex pattern of land ownership and use of Great Plains grasslands challenges native species conservation. Approaches to managing both public and private grasslands, frequently focused at the scale of individual pastures or ranches, limit opportunities to conserve landscape-scale processes such as fire, animal movement, and metapopulation dynamics. Using the US National Land Cover Database and Cropland Data Layers for 2011−2017, we analyzed land cover patterns for 12 historical grassland and savanna communities (regions) within the US Great Plains. On the basis of the results of these analyses, we highlight the critical contribution of restored grasslands to the future conservation of Great Plains biodiversity, such as those enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program. Managing disturbance regimes at larger spatial scales will require acknowledging that, where native large herbivores are absent, domestic livestock grazing can function as a central component of Great Plains disturbance regimes if they are able move at large spatial scales and coexist with a diverse array of native flora and fauna. Opportunities to increase the scale of grassland management include 1) spatial prioritization of grassland restoration and reintroduction of grazing and fire, 2) finding creative approaches to increase the spatial scale at which fire and grazing can be applied to address watershed to landscape-scale objectives, and 3) developing partnerships among government agencies, landowners, businesses, and conservation organizations that enhance cross-jurisdiction management and address biodiversity conservation in grassland landscapes, rather than pastures.

(Augustine et al. 2019, Rangeland Ecology and Management)

Recent Project

Augustine et al. 2019, Rangeland Ecology and Management

David Augustine, USDA-ARS

Ana Davidson, CSU

Kristin Dickinson, USDA-NRCS

Bill Van Pelt, WAFWA

Fauna of North America’s Great Plains evolved strategies to contend with the region’s extreme spatiotemporal variability in weather and low annual primary productivity. The capacity for large-scale movement (migration and/or nomadism) enables many species, from bison to lark buntings, to track pulses of productivity at broad spatial scales (> 1 000 km2). Furthermore, even sedentary species often rely on metapopulation dynamics over extensive landscapes for long-term population viability. The current complex pattern of land ownership and use of Great Plains grasslands challenges native species conservation. Approaches to managing both public and private grasslands, frequently focused at the scale of individual pastures or ranches, limit opportunities to conserve landscape-scale processes such as fire, animal movement, and metapopulation dynamics. Using the US National Land Cover Database and Cropland Data Layers for 2011−2017, we analyzed land cover patterns for 12 historical grassland and savanna communities (regions) within the US Great Plains. On the basis of the results of these analyses, we highlight the critical contribution of restored grasslands to the future conservation of Great Plains biodiversity, such as those enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program. Managing disturbance regimes at larger spatial scales will require acknowledging that, where native large herbivores are absent, domestic livestock grazing can function as a central component of Great Plains disturbance regimes if they are able move at large spatial scales and coexist with a diverse array of native flora and fauna. Opportunities to increase the scale of grassland management include 1) spatial prioritization of grassland restoration and reintroduction of grazing and fire, 2) finding creative approaches to increase the spatial scale at which fire and grazing can be applied to address watershed to landscape-scale objectives, and 3) developing partnerships among government agencies, landowners, businesses, and conservation organizations that enhance cross-jurisdiction management and address biodiversity conservation in grassland landscapes, rather than pastures.

(Augustine et al. 2019, Rangeland Ecology and Management)

Restoration Ecology and Burrowing Mammals

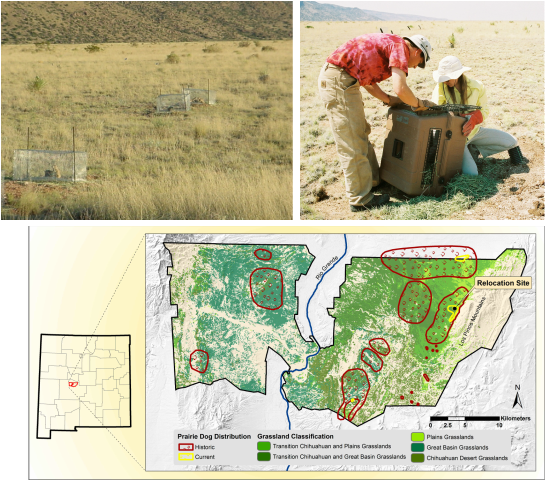

Historic (red polygons) and current (yellow polygons) distribution of Gunnison’s prairie dogs at the SNWR

Ecological restoration involves initiating the recovery of an ecosystem through human intervention. In grassland ecosystems, ecological restoration often includes restoration of natural fire regimes, reintroduction of native species, reseeding of native perennial grasses, and/or removal or reduction of domestic livestock grazing.

The central grasslands of North America that stretch from southern Canada to northern Mexico have experienced large declines in its once most abundant native herbivore: the prairie dog. Prairie dogs are considered keystone species and ecosystem engineers of this grassland system, creating important habitat for many plants and animals through their burrowing and herbivory. They also provide an important prey resource for many predators. However, as a result of century long poisoning campaigns, sports shooting, introduced sylvatic plague, and habitat loss from desertification, agricultural development, and urbanization, their populations have declined by about 98% across their range.

The loss of the ecological role of prairie dogs from much of their range has resulted in a cascade of effects throughout the grassland system, reducing grassland biodiversity (Bergstrom et al. 2013, Conservation Letters). Indeed, many species associated with prairie dogs have declined to threatened or endangered species status, including black-footed ferrets, burrowing owls, ferruginous hawks, mountain plovers, and swift foxes.

Prairie Dog Reintroduction Study at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, NM

Past Project

Ana Davidson, UNM & Sevilleta Long-Term Ecological Research Program (LTER)

Mike Friggens, UNM & Sevilleta LTER

Jon Erz, US Fish and Wildlife Service

Consistent with range-wide trends, Gunnison’s prairie dogs (C. gunnisoni) have been almost entirely eliminated from the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge (SNWR) Socorro County, NM, as a result of extensive poisoning campaigns in the 1960’s (before the refuge was established). Since these efforts, the SNWR has been missing this important herbivore from its grasslands.

Since 2005, we have relocated thousands of prairie dogs from urban areas to the SNWR. Prairie dogs now occupy five colonies across about 50 ha of the SNWR (Davidson et al. 2014, JWM; Davidson et al. 2018, Rest Ecol). The goal of this work is to: 1) help restore the SNWR grassland and its native keystone rodent, 2) study the population dynamics of the reintroduced prairie dogs over time to inform management and conservation efforts in the semi-arid parts of their range under climate change, and 3) quantify the ecological effects of the prairie dogs on the grassland landscape as they recolonize it. This project is a large collaborative effort among the SNWR, the Sevilleta Long-Term Ecological Research Program, Department of Biology at UNM, Prairie Dog Pals of Albuquerque, and the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

The reestablished colonies play an important role in education and outreach. Dr. Chuck Hayes completed his doctoral research on the physiology and demography of the reintroduced animals. Every summer undergraduates through the National Science Foundation's Research Experiences for Undergraduates Program and student interns with the Sevilleta LTER and SNWR assist in the ongoing restoration and research.

The central grasslands of North America that stretch from southern Canada to northern Mexico have experienced large declines in its once most abundant native herbivore: the prairie dog. Prairie dogs are considered keystone species and ecosystem engineers of this grassland system, creating important habitat for many plants and animals through their burrowing and herbivory. They also provide an important prey resource for many predators. However, as a result of century long poisoning campaigns, sports shooting, introduced sylvatic plague, and habitat loss from desertification, agricultural development, and urbanization, their populations have declined by about 98% across their range.

The loss of the ecological role of prairie dogs from much of their range has resulted in a cascade of effects throughout the grassland system, reducing grassland biodiversity (Bergstrom et al. 2013, Conservation Letters). Indeed, many species associated with prairie dogs have declined to threatened or endangered species status, including black-footed ferrets, burrowing owls, ferruginous hawks, mountain plovers, and swift foxes.

Prairie Dog Reintroduction Study at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, NM

Past Project

Ana Davidson, UNM & Sevilleta Long-Term Ecological Research Program (LTER)

Mike Friggens, UNM & Sevilleta LTER

Jon Erz, US Fish and Wildlife Service

Consistent with range-wide trends, Gunnison’s prairie dogs (C. gunnisoni) have been almost entirely eliminated from the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge (SNWR) Socorro County, NM, as a result of extensive poisoning campaigns in the 1960’s (before the refuge was established). Since these efforts, the SNWR has been missing this important herbivore from its grasslands.

Since 2005, we have relocated thousands of prairie dogs from urban areas to the SNWR. Prairie dogs now occupy five colonies across about 50 ha of the SNWR (Davidson et al. 2014, JWM; Davidson et al. 2018, Rest Ecol). The goal of this work is to: 1) help restore the SNWR grassland and its native keystone rodent, 2) study the population dynamics of the reintroduced prairie dogs over time to inform management and conservation efforts in the semi-arid parts of their range under climate change, and 3) quantify the ecological effects of the prairie dogs on the grassland landscape as they recolonize it. This project is a large collaborative effort among the SNWR, the Sevilleta Long-Term Ecological Research Program, Department of Biology at UNM, Prairie Dog Pals of Albuquerque, and the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

The reestablished colonies play an important role in education and outreach. Dr. Chuck Hayes completed his doctoral research on the physiology and demography of the reintroduced animals. Every summer undergraduates through the National Science Foundation's Research Experiences for Undergraduates Program and student interns with the Sevilleta LTER and SNWR assist in the ongoing restoration and research.

Here's a video of the prairie dog relocation efforts on the SNWR, created by undergraduate students working on the project.

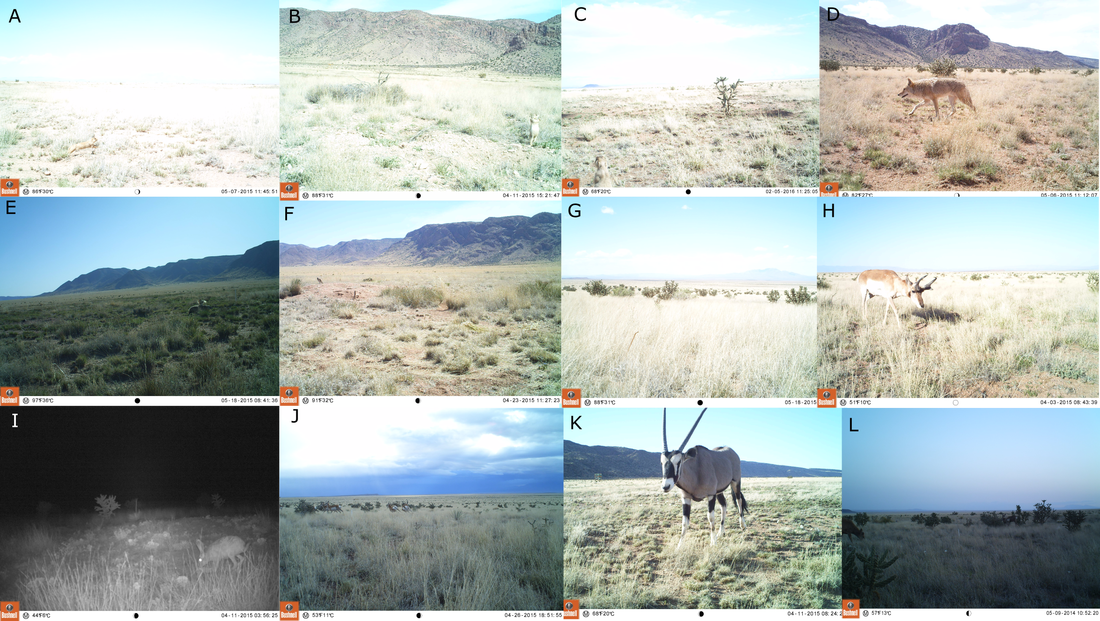

We established camera traps on and off our relocated colonies to determine if our relocation efforts are helping to restore the ecological role of prairie dogs. Our camera traps captured large numbers of photos of species associated with prairie dog colonies, including burrowing owls, badgers, desert cottontails and raptors on the prairie dog colonies compared to off-colony grassland areas. We also obtained photos that captured the behavior of vertebrate species on prairie dog colonies, such as the photo of a burrowing owl pouncing on a badger as it crosses a prairie dog colony, in attempt to chase the badger off the colony. Burrowing owls will engage in this behavior while prairie dogs are also sounding alarm calls of a predator entering a colony (image E, below). This is a neat example of multiple species working together to fend off a shared predator. Overall, our results show that the reintroductions of prairie dogs at the Sevilleta NWR are indeed helping to restore their functional role to the grassland ecosystem (Davidson et al. 2018, Rest Ecol). See also the story by NMDG&F's Share with Wildlife Program on this project (and see presentation below for more on our findings).

Photos from our camera traps at the Sevilleta NWR showing: A, B, C) prairie dogs, D) a coyote, E) a burrowing owl pouncing the back of a badger crossing a colony, F ) a burrowing owl on a mound and a spotted ground squirrel standing up next to the mound, G) a coachwhip snake looking over grass, H) a pronghorn, I) a black-tailed jackrabbit, J) pronghorn running, K) an oryx, and L) mule deer running.

Global Conservation, Biogeography and Macroecology

Human impacts on Earth’s biodiversity are occurring at unprecedented rates. Biogeography and macroecology provide ecologists with the ability to evaluate large-scale patterns and statistical distributions of biodiversity and the causal factors driving those patterns. These approaches provide broad, global-scale information for informing basic ecological theory and guiding conservation and policy.

I am applying such approaches to understanding global-scale patterns in biodiversity loss and the human impacts driving those trends. A major focus of this research centers around developing traits-based and spatially-explicit predictive models of vertebrate risk to help inform conservation. I use machine learning approaches to develop a map of the ecological pathways to extinction across mammals (Davidson et al. 2009, PNAS), and to identify the drivers and global hotspots of extinction risk in marine mammals (Davidson et al. 2012, PNAS). Through these and related projects, I am working with colleagues to uncover emerging priorities to inform global conservation action by identifying species and regions of reptiles and mammals most vulnerable to extinction and climate disruption, across the dimensions of biodiversity (Murray et al, 2014, GCB , Böhm et al. 2016, GEB, Böhm et al. 2016, Bio Con; Brum et al. 2017, PNAS). As part of this work, we have published a database on the climate change vulnerability of 1498 reptiles: Böhm et al. 2016, Bio Con. I also work with colleagues to address other basic macroecological questions as well. This includes understanding global-scale patterns and drivers of mammalian biodiversity and assemblage structure (Oliveira et al. 2016, GEB; Penone et al., Proc B).

I am applying such approaches to understanding global-scale patterns in biodiversity loss and the human impacts driving those trends. A major focus of this research centers around developing traits-based and spatially-explicit predictive models of vertebrate risk to help inform conservation. I use machine learning approaches to develop a map of the ecological pathways to extinction across mammals (Davidson et al. 2009, PNAS), and to identify the drivers and global hotspots of extinction risk in marine mammals (Davidson et al. 2012, PNAS). Through these and related projects, I am working with colleagues to uncover emerging priorities to inform global conservation action by identifying species and regions of reptiles and mammals most vulnerable to extinction and climate disruption, across the dimensions of biodiversity (Murray et al, 2014, GCB , Böhm et al. 2016, GEB, Böhm et al. 2016, Bio Con; Brum et al. 2017, PNAS). As part of this work, we have published a database on the climate change vulnerability of 1498 reptiles: Böhm et al. 2016, Bio Con. I also work with colleagues to address other basic macroecological questions as well. This includes understanding global-scale patterns and drivers of mammalian biodiversity and assemblage structure (Oliveira et al. 2016, GEB; Penone et al., Proc B).

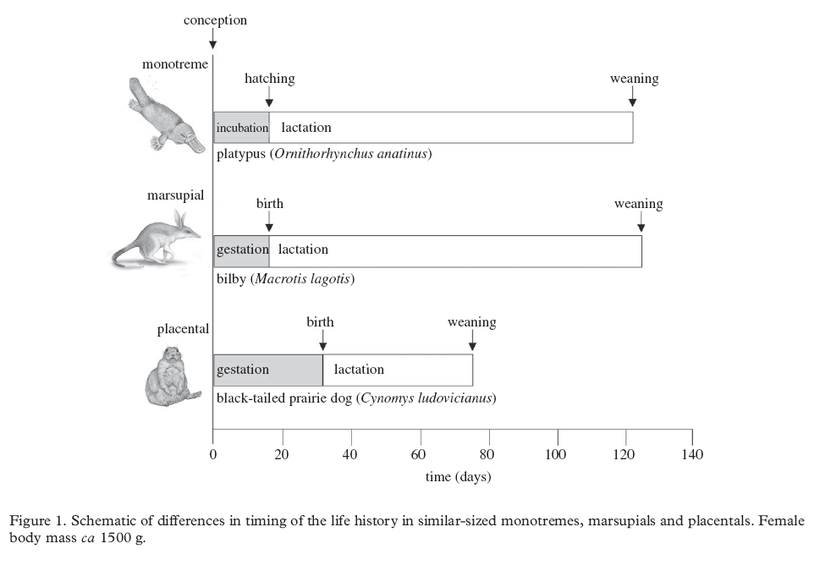

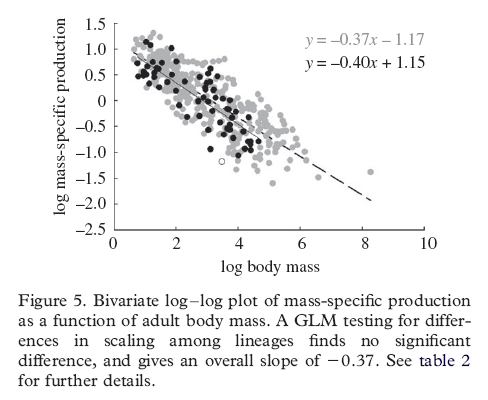

Additionally, we have worked to understand how energy is allocated to production across different mammalian lineages (Hamilton et al. 2010, Proc R Soc B , see Figures 1 & 5 below). Here, we found that despite striking differences in life histories among placental, marsupial, and monotreme mammals, the scaling of production rates is statistically indistinguishable across mammalian lineages. This suggests that all mammals are subject to the same fundamental metabolic constraints on productivity.

My colleagues and I also are taking a human macroecologcial perspective to understanding the energetic basis of human economies and its implications for economic and ecological sustainability (Brown et al. 2011, BioScience, see Figure 1 below), and to providing macroecological insights for sustainability science (Burger et al. 2012, PLoS Biology; Nekola et al. 2013, TREE; Brown et al. 2013, Ecological Engineering).